Friday, October 15, 2010

Progress on Common Core State Standards

Users of Galileo K-12 services are already familiar with the alignment of our instructional materials and assessments to the specific state standards that have been in use. Now, as we transition into the Common Core State Standards, we are drawing upon the resources from each state that helped inform the development of the Common Core State Standards while also expanding and innovating to address the greater breadth and specificity in the new standards.

To provide an example, in third grade language arts, states where Galileo K-12 is used had as few as 16 and as many as 68 standards, sometimes incorporating writing as part of the standards, and in other states having separate standards for writing. In the Common Core State Standards, third grade English/Language Arts has 92 standards for instruction and assessment. We all know that third-graders aren't being expected to learn an additional 50% more than their predecessors. The Common Core State Standards are instead providing a greater degree of specificity in identifying the skills and knowledge that a student in the third grade is supposed to master to match the progress expected of all third graders in the Common Core State Standards.

Each state adopting the Common Core State Standards will develop crosswalk materials that align its existing high-stakes assessment items and prior standards to the new standards. ATI is already engaged in that process, drawing from our nationwide experience to incorporate the proven materials in our item and activity banks in specific alignment to the Common Core State Standards expectations. These items and activities will then be available to teachers to use in identifying initial student performance on the new standards and then evaluating student needs for instruction on standards that may be different or more detailed than was present in the previous version of state standards. This is where our extensive content from multiple states will prove valuable, having a ready resource for assessment and instruction in these newly emphasized capabilities.

We are looking forward to working with all of our client districts as this new era of educational cooperation and heightened expectations of student success unfolds.

Tuesday, September 7, 2010

Five Steps Forward in Implementing Educational Reform in Your District

It is axiomatic that within this local context, success in implementing and sustaining reform efforts over the long-term is best achieved when districts and governing boards exercise local control across a broad range of decision-making activities. Among the most salient of these decision-making activities is the selection and adoption of technology-based instructional improvement systems that provide a “best fit” with the district’s educational reform and student achievement goals. An instructional improvement system is generally conceived of as a technology-based, data-driven, standards-aligned, integrated system comprised of assessment, reporting, and instructional tools that can be used to support district efforts to elevate student achievement.

As you engage in the process of selecting a new instructional improvement system or replacing an old one, here are five fundamental steps you can take to help pave the way:

Building Consensus and Identifying Roles

As the old adage goes, “buy-in is critical.” In this regard, consensus building will need to take into consideration a variety of factors including district stakeholder interests, skills and expertise, and the impact of instructional improvement system adoption on established routines, to name a few. For some stakeholders, integration of an instructional improvement system into daily routines might represent a welcome enhancement. For others, it may initially evoke a sense of uncertainty about what specific kinds of changes will likely occur within the classroom and concern about how these changes may affect established routines and approaches to ongoing instruction. Consensus building in support of efforts to select and adopt an instructional improvement system helps to ensure that the course of action is one that everyone is generally comfortable with. At the outset, consensus building activities help to identify common ground for the importance of these efforts. Moreover, consensus building activities provide a collaborative context for: 1) identifying realistic and relevant goals in relation to system use; 2) developing an agreed to set of plans and procedures for implementation; 3) managing and monitoring implementation over time; and 4) evaluating and utilizing results to inform ongoing decision-making and implementation revisions. To get thing going, formulate some basic questions:

• How will input from stakeholders be gathered and taken into consideration?

• How will stakeholders be informed of the instructional improvement system options available?

• Will there be a formal review committee or will administrators seek stakeholder input?

Determine District Goals

In order to effectively evaluate an instructional improvement system for local deployment it is essential to identify immediate and long-term educational reform goals. A starting point for this process is the formulation of a few basic questions:

• What are the overall goals of our district in using an instructional improvement system?

• What are our assessment and reporting goals?

• What are our goals for the students?

• Teachers? Administrators?

• What are our goals related to providing educational content and monitoring curriculum implementation?

Develop Criteria for Consideration

Criteria to be considered in evaluating the “best fit” between an instructional improvement system and district goals might include taking a close look at the system’s assessment, scoring and reporting, and instructional capabilities. Consideration should also be given to the extent to which the system can accommodate professional learning communities and provide flexibility both in system implementation options and adaptability to changes in standards and government requirements. Finally, the security measures, data management features, and technical requirements of the system should be thoroughly vetted.

Establish Timelines and Determine the Selection Process

Timely implementation of a new instructional improvement system is the key to promoting successful outcomes. Consequently your district will want to work backwards from the desired implementation date in planning a realistic timeline for evaluating options and selecting an instructional improvement system. To facilitate this process, a number of questions might be considered:

• Will the selection process require a request for proposal (RFP) and if so, how much time is needed to review RFP responses and move the process through district channels?

• If an RFP is not required, what selection process will be used, who is involved, and how much time is needed?

• How will our governing board be included in the process and how will their role impact the timeline?

• What post-selection tasks and customization (district pacing calendar aligned benchmarks) might impact the timeline?

Compare Technology Solutions

Local control and empowerment over educational reform is fully exercised during the evaluation of the instructional improvement system options available and the eventual decision to select and adopt a particular instructional improvement system. Becoming fully informed about the options available, their strengths and limitations is essential to the success of this process. This can be accomplished in a number of ways:

• Gather information and materials including background research and referrals.

• Interview each organization offering an instructional improvement system solution and request an online walkthrough. This will allow you to preview systems and create a short list for presentations at the district.

• Request on-site presentations so that you can see firsthand the extent to which the various options meet your district’s needs.

• Ask for access to the system and assign staff to “try out” the system.

• Carefully review written proposals and cost estimates against your criteria and talk to other districts that use the instructional improvement system under consideration.

Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Adaptive Testing

How does an adaptive test adapt? The approaches that are currently used fall into two basic categories based on whether adaptation decisions are made after every item or after a group of items. In the first case, a cumulative score is calculated each time a student completes an item. The next item is typically selected by determining the item that will provide the optimal level of information regarding the student’s ability. Once a score has been reached that provides an adequate level of measurement precision, the assessment is ended. Typically this endpoint is reached after far fewer questions than would be required to achieve a comparable level of precision on a standard or “linear” test , thus making the approach extremely efficient.

In the second case, decisions are made after administering preconfigured blocks of items rather than on an item by item basis. A typical design might specify a routing test followed by two stages, each of which involves a decision between pre-constructed item blocks optimized for lower, average, and high ability. In this design, students would complete the routing test and then be assigned to the appropriate second stage item block based on their score. After completing the second stage they would again be routed to the appropriate block of items in stage three based on their cumulative score on the routing test and the second stage. After completing the third stage the assessment would be ended and an overall score determined based on all the items completed.

What are the benefits of adaptive testing? One of the most notable is its efficiency. This is particularly true with the item by item approach. As I mentioned, an adequately precise measure of a student’s ability may typically be achieved with far fewer items than would be required for a typical “linear” test. This efficiency can make the approach far easier to use when large groups of students must be tested in a short time.

What considerations go along with the benefits? Two of the most fundamental are content control and item exposure. Both are controlled to some degree by the multi-stage design. The multi-stage design is not quite as efficient as the single-stage design. However, in those cases in which content control and/or item exposure are important considerations, the multi-stage approach may be preferred.

Content control is especially important in standards-based education. While the item by item approach is extremely efficient, the ability to ensure that all students are exposed to content reflecting standards targeted for instruction may be compromised in the item by item approach. Johnny, Suzy, and Javier may all sit down together and not be exposed to any of the same items. Suzy may have to multiply fractions while Johnny and Javier don’t. This may not be cause for concern if the test is being used for purposes of screening, but it may limit the utility of the measure if the results are being used for very specific decisions about student instructional needs. For instance, if there are instructional decisions to be made about providing instructional coaching on multiplication of fractions for Johnny and Javier, it would likely be most informative they had actually been asked to respond to the questions that Suzy was given. While Item Response Theory (IRT) may be used to estimate the probability that students have mastered these skills even if they haven’t been given the questions, actual administration of the items can afford the additional benefit allowing mistakes to be analyzed. The pre-constructed design of the multi-stage approach affords control of this issue at the expense of some efficiency.

Item exposure is particularly important when item security is a concern. The focus of the item selection algorithms on picking the optimal item for a given ability level can mean that the same limited set of items come to the top of the heap repeatedly. This is particularly true for the item by item approach. This issue can limit the utility of the assessment for repeated use because students are likely to see the same items again and again. In high stakes situations, the door is open for cheating because the items that are likely to show up become predictable. As with the content consideration, the multi-stage approach provides some control over this issue at the expense of efficiency.

The combination of strengths and unique considerations involved with adaptive testing point to some particular uses for which it would be a strong choice. One of the most notable is screening. The efficiency with which an adaptive test can provide a reliable measure of ability make it a good choice when the issue at hand is deciding whether a student should enter into a particular instructional group or class. The degree of content control provided by a multi-stage approach could provide more granular information when the decision at hand is whether a child should be given additional help on a specific skill or set of skills.

ATI is current working on a module to support adaptive testing. The module will support the the item by item and multi-stage approaches. Provision of these options will allow districts to take advantage of the strengths provided by adaptive testing when they are designing an assessment program that will best meet their needs.

Tuesday, August 17, 2010

ATI Develops New Technological Capabilities to Assess Literacy in Early Childhood

Over the last decade, childhood literacy has become an important topic on a national and state level. In 1997 and 2002, Congress convened two national panels (the National Reading Panel and the National Early Literacy Panel) to provide research-based recommendations on how to improve reading achievement in early childhood. The reports issued by these panels are available at www.nationalreadingpanel.org and www.nifl.gov. Individual states are also implementing initiatives related to early childhood literacy. For example, Arizona recently passed a bill which calls upon a statewide task force to provide recommendations for a set of statewide assessments to measure students’ reading abilities in grades one and two. The bill also requires school districts to screen students in preschool through second grade for reading deficiencies, providing an opportunity for early intervention during this critical time period. Along with these evaluations, the bill requires that students reading far below grade level at the end of third grade are not promoted to fourth grade. Retained students must be provided with targeted intervention such as summer school reading instruction, online reading instruction, a different reading teacher, or intensive reading instruction during the next academic year.

To support national and state early childhood literacy initiatives, ATI has been working to develop a set of assessments targeting the critical aspects of reading for grades K through three. By providing valid, reliable, standards aligned assessments, ATI can assist districts and schools by identifying students with reading deficiencies and suggesting appropriate areas for intervention. ATI also supports targeted interventions and online reading instruction through Instructional Dialogs and other intervention materials that allow students to practice early literacy skills. Assessing the early literacy skills of very young children presents some unique challenges. For example, many standards related to early literacy are not best assessed using a standard text-only, multiple-choice item. In addition, very young children often cannot read even simple text. For these reasons, the development of new technological capabilities and innovative item types has been an important part of ATI’s work.

One new and exciting technological capability developed by ATI for these assessments is the ability to include audio material in items. The audio capability makes it possible to create computer-administered items for children who are not yet able to read. Instead of the teacher reading the item aloud, the child can listen to pre-recorded instructions, questions, and answer choices. This capability enables a more standardized presentation of items and makes the assessment easier to administer. In addition, the audio capability allows the direct assessment of standards that address the awareness or manipulation of the sounds in spoken language (phonemic awareness) without teacher involvement.

Another newly developed ATI technological capability is the ability to present text for a predetermined time period. This capability has been crucial to the development of a new innovative item type designed to assess reading fluency (a concept related to reading rate). Previously, assessment options for reading fluency were limited to one-on-one testing and scoring procedures requiring subjective judgment. This new capability represents a major advance in ATI’s coverage of early childhood standards by enabling online assessment of reading fluency and automated scoring.

Two more technological capabilities have been developed by ATI to tailor the assessment process for very young children. First, to keep children engaged and to encourage them to progress through the assessment, visually engaging scenes have been developed that slowly appear piece by piece as a reward after each question is answered. Second, the new assessments and item types have been designed to be compatible with portable tablet computers that employ touch screen technology as well as standard desktop computers. By facilitating the assessment of young children, these new technological capabilities developed by ATI will support districts and schools in implementing literacy assessments and interventions in early childhood.

Tuesday, July 20, 2010

District Suggestions for New Items

ATI has stringent guidelines for creating items. When making suggestions for new items, there are a number of considerations that a district may find useful. Suggestions for new items are likely to benefit the district most when they focus on the measurement of a specific skill or capability. If the district curriculum includes a particular capability that is not currently well represented in ATI item banks, suggesting the inclusion of additional items assessing the skill in question will be beneficial as long as the skill suggested aligns to the standard. At times, textbooks contain concepts which do not align to any state standards. In order to maintain the validity of ATI assessments, only items which align to a specific state standard may be added to ATI’s assessment bank. The more specific a request provided by a district, the more likely that ATI’s writers will be able to produce the exact items a district desires.

Suggesting stylistic changes is generally less useful. ATI does develop items specifically aligned to the various styles of statewide assessments. ATI, as well as states testing companies, have specific guidelines for measuring reading level. Many items use specific wording in order to maintain appropriate grade-level readability. For example, the phrase “past tense” will not be used on a third grade test since the word “tense” has a reading level ranking of sixth grade. It is important to ensure that items on local benchmark and formative assessments not be limited to a particular style. Only practicing items using specific wording when learning a new concept may cause challenges for students later. Even state released items change their wordings from year to year. One year the first grade word problem may include the phrase “in all” and the following year it may include the phrase “altogether”. It is important for students to practice items using both phrases. In addition, as items become closer in style to a statewide test, the danger that test outcomes will be contaminated by the phenomenon of “teaching to the test” increases. Benchmark and formative assessments are intended to measure the mastery of standards, not merely the ability to respond to items written in one particular style.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

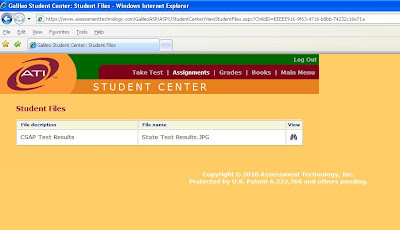

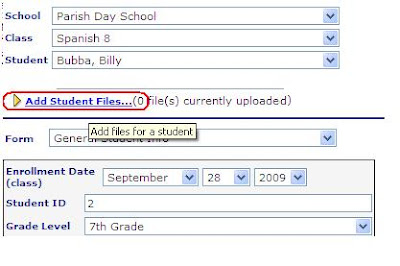

Student File Attachment

On the Student Demographics page, there’s a link to “Add Student Files…” In addition, there’s an indicator as to how many files are attached so users don’t have to open the interface to find out.

When you click the "Add Student Files..." link, the Student Files page opens. There's no limitation as to the file type that can be added, and, currently, no size limit. The option is given to add a file description. The final step is attaching the file and selecting the “Add” button.

When you click the "Add Student Files..." link, the Student Files page opens. There's no limitation as to the file type that can be added, and, currently, no size limit. The option is given to add a file description. The final step is attaching the file and selecting the “Add” button.Monday, June 21, 2010

Preparing Your 2010-2011 Rosters

With the arrival of summer ATI staff members responsible for Galileo student data management shift their focus to, of all things, fall. This focus is primarily on new classes, rosters, and accommodating all staff changes a district may undertake throughout the summer.

For districts new to Galileo, the best way to create your class lists and rosters is through Galileo Data Import (GDI). The GDI process involves three basic steps:

- Districts provide an export from their Student Information System (SIS) that lists all classes, teachers, and students within the district.

- ATI staff import this data to a test database and perform a thorough quality assurance review – any problems are resolved with the district before the data is imported (step 3) into the live Galileo database.

- ATI staff import the district-provided information directly into Galileo K-12 Online.

Detailed instructions for GDI can be found in the Tech Support section of Galileo K-12 (and Preschool) Online, as well as at the following links:

Preschool: http://www.ati-online.com/pdfs/ImportInstructionsPre-K.pdf

K-12: http://www.ati-online.com/pdfs/ImportInstructionsK-12.pdf

As you prepare your 2010-2011 program year data for import, please remember the following important points:

- Be sure to include all required information in your import.

- Optional information is not required in the Galileo database, but failure to include this information may adversely affect future report filtering.

- Any omitted optional data can be imported at any time throughout the program year, either as part of GDI or as a separate process – contact ATI for more information.

- If TeacherID or StudentID fields change within your SIS, please notify ATI prior to providing any import files to ensure proper transition within the Galileo database. Large-scale ID changes may require extra processing time so please notify ATI as far in advance as possible so we can help you plan accordingly.

- Due to new class structures and teacher assignments, the quality assurance process is typically longest during the first upload of the year. Getting uploads underway as soon as data is available will help ensure adequate processing time before your first assessments of the year.

- Providing ‘shell’ data with class structures and teachers as soon as they are entered into your SIS this summer will provide opportunity to perform thorough review of class alignment, course codes and teacher assignments. This will speed the processing of files containing student enrollment in the fall.

Please refer to the links above for more details about the import process.

Friday, June 11, 2010

ATI and the Common Core Standards

The development of these standards has already influenced the standards revision process in many states. Those states currently in the process of revising and updating their local standards will now have an opportunity to consider how the Common Core Standards will inform their new educational objectives, whether through direct adoption or mapping of common goals, as part of a collective effort to raise student achievement across the nation.

Assessment Technology, Inc. is eagerly anticipating the opportunity to assist districts using Galileo K-12 Online in the transition to new state standards and in aligning their standards with the Core Curriculum Standards. ATI’s existing process of specification to develop precise assessment and instructional content is the key factor in the process to manage this transition.

As we develop materials and questions to instruct and measure student success on the state standards we write specifications that not only accurately and effectively measure the standard, but further refine the process by defining the particular skills or knowledge inherent in components of that standard. This fundamental, systemic approach places the full content of the Galileo K-12 Online banks in a format that allows for detailed and precise mapping, or in this case remapping, of assessment items and instructional materials to particular characteristics of state standards.

The diversity of our 74,000+ item bank and 1,500+ Instructional Dialogs draws on our experience writing to measure the standards present in each state and then finding the exact mapping appropriate to those items in other states where that same skill or knowledge is demanded. Rather than applying generic items at the most broad levels, we have defined the specifications to allow lessons, activities, and items to be used exactly where they are needed. This expertise will be a tremendous asset as ATI works with our partner-districts in the transition from the generation of standards we have all been using over the last five to eight years, to the new state or Common Core Standards as they are adopted by the states.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Interim and End-of-Course Examinations in Standards-Based Education

Interim and End-of-Course Examinations

The purposes of interim and end-of-course assessments have been understood for a very long time. We revisit them here to differentiate course assessments from standards-based assessments. The discussion of differentiation provides a foundation for integrating the two forms of assessment to promote student learning.

Interim and end-of-course examinations are designed to assess knowledge and skills targeted in course instruction. Interim examinations assess knowledge and skills covered during part of a course. For example, an instructor may decide to administer a mid-term examination half way through a course. The mid-term examination will cover material addressed in the first half of the course. The end-of-course or final examination may cover material reflecting the entire course, or it may cover material presented since the previous interim examination.

Course Examinations and Accountability

Although course examinations have always played a role in guiding instruction, their role in accountability has also been extensive. Moreover, the importance of accountability increases as children progress through school. Interim and end-of-course assessments hold the student accountable for learning what has been taught. As students advance through the grades, teachers place increasing responsibility for learning on student shoulders. The teacher’s responsibility is to provide opportunities to learn the material presented. The student is responsible for learning the material. Interim and end-of-course examinations provide information on the extent to which students have effectively met their responsibility for learning.

As more and more responsibility for learning is assigned to the student, interim and end-of-course examinations increasingly become high stakes assessments. The consequences associated with different performance levels on these assessments significantly impact future instructional options that may be available to the student. Students who fail course examinations will likely fail the course and as a consequence not receive credit for taking the course. Failure may require that the student take the course a second time. In some cases, poor performance on course examinations precludes the opportunity to take certain advanced courses. Poor performance on course examinations may also limit options for higher education. Sometimes failure experiences lead students to conclude that continued pursuit of education is not worth the effort. One consequence associated with this conclusion is an unacceptably large high school dropout rate.

Standards-based educational practice offers an alternative to traditional practice related to course examinations. In standards-based education, high stakes assessment is typically limited to consequences associated with performance on a statewide test. The principal purpose of local standards-based assessments is to provide information that can be used to guide instruction. Data from benchmark and formative assessments are used to plan interventions to promote further learning. The student has the ultimate responsibility for learning. However, the teacher assumes greater responsibility than that typically required in the absence of a standards-based initiative. For example, if a benchmark assessment reveals that a student is at risk for not meeting standards on a statewide test, an intervention may be undertaken to bring the student on course to meet standards. This is in direct contrast to the situation associated with interim and end-of-course assessments, in which the responsibility of mastering material is primarily on the shoulders of the student, and the interim or end-of-course assessment simply indicates to the student whether or not he or she was successful in achieving that goal. The discussion that follows suggests changes in the use of course examinations that make it possible to employ these examinations within the context of standards-based initiatives designed to elevate student achievement.

Standards-Based Course Examinations

Typically interim and end-of-course examinations are informal examinations constructed at the classroom level for the purpose of assessing student proficiency related to material covered in the course and presented in the class. Additional benefits can be derived from these assessments to the extent that they can be linked to standards-based procedures designed to enhance learning.

Informal interim course examinations are like the short formative assessments used in standards-based education in that the psychometric properties of both forms of assessment are generally not examined. In both cases the number of students taking the assessments is generally too small to support statistical analyses necessary to establish the psychometric properties of the instruments. Another similarity is that both forms of assessment are generally constructed by classroom teachers. The fact that the assessments are teacher-constructed helps to ensure that the assessments reflect what has been taught. Major differences include the fact that course examinations are not required to be aligned with standards whereas formative assessments used in standards-based education are required to be aligned to standards. In addition, course examinations are not necessarily used extensively to guide instruction whereas the central purpose of formative assessments is to guide subsequent instructional planning.

In order to apply informal course examinations in standards-based education, it would be necessary to ensure that the assessments were used not only to document what had been learned, but also to inform instructional decisions designed to elevate learning. To make this happen, the items in the examinations would have to be aligned to standards. In addition, instruction would have to be planned based on assessment results. Typically an upcoming course examination is preceded by instruction including a review of material previously presented. This instruction-assessment sequence is consistent with standards-based educational practice. However, in standards-based education, it is also important to ensure that assessment results are used to guide future instruction. Inclusion of this component of the assessment-instruction sequence increases the potential contribution of course examinations to student learning.

In some cases, interim and end-of-course examinations are administered to large numbers of students enrolled in multiple sections of the same course. These examinations are often taken by sufficient numbers of students to support psychometric analyses examining reliability and validity. Interim and end-of-course examinations that are subjected to psychometric analyses are like benchmark assessments used in standards-based education. Benchmarks are designed to provide reliable and valid assessments aligned to standards reflecting the district curriculum. Benchmarks indicate the extent to which standards targeted for instruction at successive time periods have been mastered. They also are used to forecast performance on upcoming statewide assessments. Interim and end-of-course examinations can function as benchmarks if the items included in the examination are aligned to standards and if reliability and validity are established. For example, if an interimor end-of-course assessment is to be used to forecast performance on a statewide assessment, then the assessment must be long enough to achieve acceptable reliability levels, and its validity, or effectiveness in forecasting statewide assessment performance, must be established.

Conclusion

Interim and end-of-course examinations support long-held views regarding the responsibilities of teachers and students related to learning. The responsibility of the teacher is to provide opportunities for students to learn. The responsibility of students is to take advantage of those opportunities in ways that will enable them to achieve their full potential. These views have made a significant contribution to the foundations of American education, and they remain critical components of our educational system. Yet, rapid advances in technology, the explosion of knowledge in the information age, and the advent of the global economy have called for new approaches to education that will lead to elevated achievement necessary to maintain a competitive edge in the new world that confronts us. The challenge of today is not merely to judge the achievements of students who have been given learning opportunities. It is to elevate the achievement of all students.

Standards-based education has clarified the nature of this challenge and the possible approaches that can be taken to meet the challenge. It has provided standards representing valued educational accomplishments. It has produced evolving assessment technology to measure the attainment of standards. It has introduced the power of measurement technology into local assessment programs, and it has made it clear that the national goal of elevating student achievement is attainable. The task ahead related to interim and end-of-course assessments is to link assessment to measure student achievement with assessment to guide instruction in ways that will raise achievement to new levels. This post has described some of the ways in which linking might occur.

Monday, May 10, 2010

Pretests and Posttests

Uses of Pretests and Posttests

As its name implies, in education a pretest is an examination given prior to the onset of instruction. By contrast, a posttest measures proficiency following instruction. Pretests and posttests may serve a number of useful purposes. These include determining student proficiency before and after instruction, measuring student progress during a specified period of instruction, and comparing the performance of different groups of students before and after instruction.

Determining Proficiency Before or After Instruction

A pretest may be administered without a posttest to determine the initial level of proficiency attained by students prior to the beginning of instruction. Information on initial proficiency may be used to guide early instructional planning. For example, initial proficiency may indicate the capabilities that need special emphasis to promote learning during the early part of the school year. A posttest may be administered without a pretest to determine proficiency following instruction. For example, statewide assessments are typically administered toward the end of the school year to determine student proficiency for the year.

The design of pretests and posttests should be informed by the purposes that the assessments are intended to serve. For example, if the pretest is intended to identify enabling skills that the student possesses that are likely to assist in the mastery of instructional content to be covered during the current year, then the pretest should include skills taught previously that are likely to be helpful in promoting future learning during the year. Similarly, if a posttest is intended to provide a broad overview of the capabilities taught during the school year, then the assessment should cover the full range of objectives covered during that period. For instance, the posttest might be designed to cover the full range of objectives addressed in the state blueprint.

Measuring Progress

A pretest accompanied by a posttest can support the measurement of progress from the beginning of an instructional period to the end of the period. For example, teachers may use information on progress during the school year to determine whether or not proficiency is advancing rapidly enough to support the assumption that students will meet the standard on the upcoming statewide assessment. If the pretest and posttest are to be used to measure progress, then it is often useful to place pretest scores on a common scale with the posttest scores. When assessments are on a common scale, progress can be assessed with posttest items that differ from the items on the pretest. The problem of teaching to the test is effectively addressed because the item sets for the two tests are different. More specifically, it cannot be claimed that students improved because they memorized the answers to the specific questions on the pretest. Item Response Theory (IRT) provides one of a number of possible approaches that may be used to place pretests and posttests on a common scale. When IRT is used, the scaling process can be integrated into the task of estimating item parameters. Integration reduces computing time and complexity. For these reasons, ATI uses IRT to place scores from pretest, posttests, and other forms of assessment on a common scale.

Comparing Groups

A pretest may be given to support adjustments needed to make comparisons among groups with respect to subsequent instructional outcomes measured by performance on a posttest. Group comparisons may be implemented for a number of reasons. For example, group comparisons are generally required in experimental studies. In the prototypical experiment, students are assigned at random to different experimental conditions. Learning outcomes for each of the conditions are then compared. Group comparisons may also occur in instances in which there is an interest in identifying highly successful groups or groups needing additional resources. For example, group comparisons may be initiated to identify highly successful classes or schools. Group comparisons may be made to determine the extent to which instruction is effective in meeting the needs of NCLB subgroups. Finally, group comparisons involving students assigned to different teachers or administrators may be made if a district is implementing a performance-based pay initiative in which student outcomes play a role in determining staff compensation.

If a pretest and posttest are used to support comparisons among groups, a number of factors related to test design, test scheduling, and test security must be considered. Central concerns related to design involve content coverage and test difficulty. Both the pretest and the posttest should cover the content areas targeted for instruction. For example, if a particular set of objectives is covered on the pretest, then those objectives should also be addressed on the posttest. Targeted content increases the likelihood that the assessments will be sensitive to the effects of instruction. Both the pretest and the posttest should include a broad range of items varying in difficulty. Moreover, when the posttest follows the pretest by several months, the overall difficulty of the posttest generally should be higher than the difficulty of the pretest. Variation in difficulty increases the likelihood that instructional effects will be detected. For example, if both the pretest and the posttest are very easy, the likelihood of detecting effects will be reduced. In the extreme case in which all students receive a perfect score on each test, there will be no difference among the groups being compared.

When group comparisons are of interest, care should be taken to ensure that the pretest is administered at approximately the same time in all groups. Likewise the posttest should be administered at approximately the same time in all groups. Time on task affects the amount learned. When the time between assessments varies among groups, group comparisons may be spuriously affected by temporal factors.

Test security assumes special importance when group comparisons are made. Security is particularly important when comparisons involve high-stakes decisions. Security requires controlled access to tests and test items. Secure tests generally should not be accessible either before or after the time during which the assessment is scheduled. Galileo K-12 Online includes security features that restrict access to items on tests requiring high levels of security. Security imposes a number of requirements related to the handling of tests. When an assessment is administered online, the testing window should be as brief as possible. After the window is closed, students who have completed the test should not have the opportunity to log back into the testing environment and change their answers. Special provisions must be made for students who have missed the initial testing window and are taking the test during a subsequent period. When a test is administered offline, testing materials should be printed as close to the scheduled period for taking the assessment as possible. Materials available prior to the time scheduled for administration should be stored in a secure location. After testing, materials should either be stored in a secure location or destroyed.

Misuse of Pretests and Posttests

The misuse of tests generally occurs when tests are used for purposes other than those for which they are intended. This is true for pretests and posttests as well as for other kinds of assessments. As the previous discussion has shown, pretests and posttests are designed to serve a limited number of specific purposes. When these assessments are used for other purposes, there is a risk that the value of the information that they provide will be compromised. For example, if a pretest or posttest were to be used as a customized benchmark test, assessment results could be misleading. Conversely, if a customized benchmark assessment were used as a pretest or posttest, the credibility of assessment results could be compromised.

The central purpose of customized benchmark tests is to inform instruction. This purpose carries with it implications for test design and implementation that are generally not compatible with the purposes served by pretests and posttests. Benchmark assessments are interim assessments occurring during the school year following specified periods of instruction. Benchmark assessments provide a measure of what has been taught and an indication of what needs to be taught to promote further learning. Pretests and posttests are generally not well suited to serve as benchmarks because they often include constraints that limit their use in informing instruction. For instance, it is useful for teachers to analyze performance on benchmark assessment items to determine the kinds of mistakes made by students. This information is subsequently used to guide instruction. Pretests and posttests often call for high levels of security that curtail the analysis of specific items for purposes of informing instruction.

The temptation to use pretest and posttests as benchmarks may stem from the laudable motive of reducing the amount of time and resources devoted to testing students. Reductions in testing time increase the time available for instruction and reduce the costs associated with assessment. These are desirable outcomes. Unfortunately there often is a heavy cost associated with using assessments for purposes for which there are not intended. Often the cost is to compromise the validity of the assessments. When validity is compromised, results can be misleading. Pretests and posttests are valuable assessment tools. When they are appropriately designed, they can make a highly significant contribution to the success of an assessment program.

Wednesday, May 5, 2010

What Constitutes an Effective, Research-Based Instructional Improvement System?

According the Phase 2 RTTT application, “instructional improvement systems are technology-based tools and other strategies that provide teachers, principals, and administrators with meaningful support and actionable data to systemically manage continuous instructional improvement, including such activities as: instructional planning; gathering information through formative assessments, interim assessments, summative assessments, and looking at student work and other student data; analyzing information with the support of rapid-time reporting, using this information to inform decisions on appropriate next instructional steps, and evaluating the effectiveness of the actions taken. Such systems promote collaborative problem-solving and action planning; they may also integrate instructional data with student level data such as attendance, discipline, grades, credit accumulation, and student survey results to provide early warning indicators of a student’s risk of educational failure.”

As part of our efforts to support states and districts in addressing the challenges and opportunities inherent in the selection and implementation of an instructional improvement system, we have prepared a resource document. The resource document is located at http://www.ati-online.com/pdfs/researchK12/Meeting_IIS_Requirements.pdf. The material within the document is intended to assist local education agencies (LEAs) and State Departments of Education (SDEs) currently using or seeking to use an instructional improvement system to clearly define for themselves and in grant writing the attributes of the system and the contributions the system can make to LEA instructional improvement efforts.

We encourage you to take a look at the resource document; see if the information contained within it is addressed by your current system; and use the document as a guide in your ongoing efforts to improve the impact of your education initiatives on student learning. If you have questions or ideas that you would like to share please do so in this blog and/or contact me at Assessment Technology Incorporated.

Jason K. Feld, Ph.D.

1-800-367-4762 (Ext 121)

Jason@ati-online.com

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

Finding Balance: Designing a Balanced (and Effective) Assessment System

Starting a discussion of a balanced assessment system begs the question about what exactly must be balanced with what. In short, the balanced assessment notion argues that assessment systems have many different purposes and that those purposes must be balanced without one overwhelming the other. The need for an administrator to evaluate the efficacy of a school within the district must be balanced with the teacher’s need to plan based on information about his/her student’s mastery of standards which must be balanced with a student’s need for feedback on his/her work. NCLB and RTT also emphasize the need for state and federal government oversight of schools to be added to the mix.

Balancing all of these different components naturally requires a system that contains different types of assessments. One type of assessment cannot really adequately serve all the different needs. An assessment designed to provide an overview of progress during the entire year must necessarily cover a wide range of topics. The number of items that would be required for that type of coverage would be, to say the least, a bit unwieldy as a tool to provide data for classroom planning. In contrast, informing decision making for the teacher requires an instrument that is targeted to the specific topics that are the focus of instruction at that moment.

When an assessment system involves multiple different types of assessments, each instrument must be specifically designed for its function within the bigger picture. Using an instrument for a purpose other than what it has been designed, while at times being tempting, is a sure route towards making decisions based on data that is invalid. While different instruments are required, they must play well together in order to provide the balance that is sought. This part of the design of an assessment system can be the trickiest as there are many potential pitfalls. One of the most common sources of difficulty is the lack of a common underlying framework dictating the kinds of assessments to be used and the purposes served by each type of assessment. Put another way, it would make little sense for the formative component to be aligned to a different instructional plan that the quarterly benchmark assessments. An administrator who is following student progress by observing results on formative assessment could be in for quite a surprise when state tests are administered. In order for the different measures of student proficiency that are part of a balanced assessment system to present a complete and sensible picture, they have to be aligned to the standards targeted for instruction. It is also important that all components of the assessment system provide valid and reliable results. If classroom formatives aren’t producing reliable results then they don’t contribute to the overall picture in a dependable way and can produce a misleading impression. It should be noted that reliability of an assessment is something that must be evaluated on an ongoing basis. It has been well established in the literature that items that perform one way for a group of students can behave entirely differently for a different group of students.

ATI advocates and supports a balanced approach to the implementation of an assessment system. A complete and balanced picture of student achievement that meets the needs of administrators, teachers, students and parents is fundamental to increasing student achievement. Districts design benchmarks to be specifically aligned to the scope and sequence of their curriculum. A similar process is used to ensure that formatives are aligned to district instructional objectives. Benchmarks and formatives may be assembled together to form a complete picture of student learning that is well suited to determining if students are making progress overall in a school or particular class. Performance of items is also continually evaluated in order to determine how the instruments are performing with the students who are assessed.

How has the notion of a balanced assessment system impacted your district’s assessment practices?

Thursday, April 8, 2010

Instructional Dialogs and Formative Items for Enrichment and Remediation

How can the needs of all three groups be addressed? One option for teachers using Galileo Online Instructional Dialogs and formative assessments is to identify student proficiency on an Instructional Dialog or quiz drawing on their current grade level. Those students who struggle with the concept may then be assigned Instructional Dialogs and quizzes drawing on materials from earlier grades, while the students who have demonstrated proficiency appropriate to their current grade, can be given opportunities to enrich and expand their understanding with work from similar objectives at the next grade level.

As an example, a third grade standard asking students to know multiplication and division facts through 10 could be complimented by remediation in the second grade standard of multiplication by 1, 2, 5, 10,and expanded, for those students who are ready, with fourth grade work in the multiplication of two-digit numbers by two-digit, and multiple-digit by one-digit. No new materials, licenses or texts are needed. The standards for all grades for each state are assigned across the district. Teachers have access allowing them to reach forward or back within the state standards to access the Instructional Dialogs and quizzes that can help reinforce core knowledge or introduce concepts and challenges appropriate to students' current development and knowledge.

This opportunity is not limited to math. In English language arts, the recurring standards are engaged by providing grade appropriate reading content. Students may be instructed and assessed in similar standards of theme, characterization, and vocabulary from context, but a teacher may enhance learning by assigning to each student texts and questions on these common elements with readings that are best suited to the current proficiency in vocabulary and reading fluency of the individual student. By exploring the opportunities afforded by using common standards across multiple grade levels, teachers are able to increase the variety and developmental appropriateness of instructional content and assessment in the effort to foster student successes.

To get more information on how to utilize multi-grade resources for instruction and assessment, please contact the Educational Management Services Department at Assessment Technology, Incorporated.

Monday, April 5, 2010

Why did student scores go down on the most recent assessment?

Galileo DL scores are scale scores, and in Galileo K-12 Online the DL scores for interim assessments within a given grade and subject are all put on the same scale, so that the scores on different assessments can be compared meaningfully. The way this is accomplished is by relying on the item parameter estimates for the items that appear on the assessments. Item parameters (described in a previous blog) summarize various aspects of the way an item performs when students encounter it on an assessment, including its relative difficulty. When student DL scores for an interim assessment are calculated, the algorithm takes into account both the number of items the student got correct and the relative difficulty of the items on the assessment.

Consider a situation in which two students take two different assessments in 5th grade math. Both students get 65% correct, but by chance Assessment A, which was taken by Student A, was much more difficult than Assessment B, taken by Student B. If you know that there was a difference in the difficulty of the assessments, it doesn’t seem fair that both students should get the same Development Level score based on the score of 65% correct. The algorithm that calculates DL scores takes the relative difficulty of the assessments into account, and in this scenario Student A would end up with a higher DL score than Student B.

Now apply this situation to a series of interim assessments taken by the same set of students. Suppose, for example, the average student raw score was 65% correct on both the first and second interim or benchmark assessments. If the second assessment was more difficult, student DL scores will go up relative to the first. In fact, it’s possible for student DL scores to go up even if their raw scores drop a bit relative to the first assessment if the second one was much more difficult than the first. And, sometimes, student DL scores will go down on a second assessment. This can happen if it was easier, in terms of item parameters, than the first assessment and student raw scores either stayed the same, went down a bit, or only improved slightly but not enough to account for the relative ease of the second assessment.

That brings us to the most important point. If student DL scores drop rather than increase, it is important to identify which skills or concepts the students are having difficulty with and then to do something about it, via re-teaching, intervention, or whatever the best course of action seems to be given the situation and the available resources. There are at least three Galileo K-12 Online reports that are helpful in this regard: the Intervention Alert, the Development Profile, and the Item Analysis report, especially when run with the ‘detailed analysis’ display. All of these indicate student performance on specific skills and therefore provide a starting place for improving student performance.

Monday, March 29, 2010

Custom Test Reporting

Galileo K-12 Online features a variety of test reports that can be run at the student, class, school and district level. The new Custom Test Report adds flexibility by guiding users through the process of generating personal queries to export student-level demographic and test information from the Galileo K-12 Online database. Custom Test Reports can be run for single or multiple tests, including tests spanning program years.

The Custom Test Report can be accessed in the new Reporting menu under the ‘Custom’ heading:

In the Custom Test Report screen, you create a new report by clicking the ‘Create Custom Test Report’ link:

The first step in generating a custom report in Galileo is to select the desired data fields. Student demographic information and data from external assessments such as state or national tests (e.g. DIBELS, TerraNova, SAT) are accessed via Galileo Forms. Galileo Forms can also contain fields for any data desired by the district, provided either as part of a Galileo Data Import or a separate upload.

Once the desired form is selected form fields can then be selected for inclusion in the report, as shown in the following screenshot:

As shown, it is also possible to individually include the school, class, and/or teacher in the report.

Once all demographic and form data is selected, student performance data from assessments that were administered within Galileo K-12 Online are added to the report. This screenshot shows selection of the desired tests within a teacher-level library for inclusion in the report:

There are multiple options available for data inclusion and report generation. These are shown in the above screenshot. For example, a report can be generated that includes each student’s answers to test questions, and/or the correct answers. Reports can also contain cut scores, DL scores sum score, percentile, percent correct and performance levels.

Once the report settings are chosen, enter the desired delimiter (the default is comma) and file name and click the ‘Create File’ button as in the screenshot below. It is not necessary to enter a file extension, all reports generated with this feature receive the .txt extension, though the data is typically manipulated by opening in Excel.

Once the ‘Create File’ button has been clicked, you then use the ‘Custom Test Report Activity’ link at the top of the page to monitor report generation. Custom reports are generated using message queuing, meaning you do not wait for your report to appear on the screen – when the system has generated the report, the name will appear on the monitoring screen and the report is then available for download:

Manipulating the file in Excel involves just a few steps:

- Save the file to your local computer

- Open Excel

- Use the Open File function within Excel, be sure to include ‘All Files (*.*)’ in your search

- The Text Import Wizard will start automatically once you choose the downloaded file

- Identify the file as ‘Delimited’ in step 1

- Identify the comma delimiter in step 2

- Simply click ‘Finish’ in step 3

- Identify the file as ‘Delimited’ in step 1

A sample screenshot is shown here – the data is now ready for additional manipulation, sorting, filtering or reporting.

Monday, March 15, 2010

Q&A with Robert Vise, Ph.D. with Pueblo City Schools

Pueblo City Schools, through the implementation of a community-led strategic plan that began in 2007, worked to recreate the District from the ground up. Today, Dr. Robert Vise Executive Director of Assessment and Technology at Pueblo City Schools, in Pueblo, Colorado says the District is offering professional development for all staff, applying a four phase implementation model, and utilizing the tools and technology available within Galileo K-12 Online.

What were the main things that the District implemented that you believe were responsible for your success?

We took incremental steps during the first year of implementation. They were called phases.

Phase One consisted of:

a. Building administrator and lead teacher training.

b. Building training only on what Galileo was and how to administer benchmark tests.

c. Cohort of teachers to select benchmarks to be tested based upon our curriculum mapper.

d. Cohort of teachers review benchmark tests before publishing.

a. Training all staff in the analysis of benchmark tests.

b. Individualizing instruction based upon the results.

a. Expanding administrators and teachers usage of various reports.

b. Expanding into the use of Instructional Dialogs.

a. Creating formative tests in other subject areas.

b. Also, working with Americas Choice, incorporating their pre and posttests

in math and literacy to measure growth using their initiatives.

Students were identified based upon their Individual Development Plan. Students who were not proficient were provided additional instruction and safety nets such as different forms of additional instruction. This could be a tier two or tier three intervention such as Navigator Literacy, Navigator Math, Lindamood-Bell reading instruction, and after school tutoring. And teachers were directed to use the Galileo K-12 Online Benchmark Results report and the three reports within.

What advice would you give to other districts who might want to implement an approach like yours?

Work heavily in the professional development for all. Also, work with administrators to fully understand the reports and to monitor teacher use of Galileo components through class walk throughs and Professional Learning Communities.

Anything else you would like to add?

The staff at ATI has been extremely helpful along the way. When we want something changed in the system or added, they are responsive. Best vendor I have worked with.

Tuesday, March 9, 2010

What standards will be assessed on the District Benchmark Assessment?

As your next assessment window approaches we recommend that you take some time to analyze this powerful report and reflect on the instruction that has most recently occurred in your class.

As your next assessment window approaches we recommend that you take some time to analyze this powerful report and reflect on the instruction that has most recently occurred in your class.Monday, February 15, 2010

ATI hosted the “Elevating Student Achievement Seminar: Exploring What Works” in Denver, CO on February 3. One of the goals of the seminar was to allow districts to come together to share their experiences in implementing an instructional improvement system (e.g., Galileo). It was clear there are numerous benefits in using data to drive instruction when also tied with professional learning communities. One area in particular is collaborating for student success. An important aspect of collaboration is to improve instructional practices and student achievement based off of assessment results. During collaboration time, teachers and teaching teams use assessment (e.g., benchmark and formative tests) data to evaluate student learning and plan interventions as a group when they find students are not learning the standard or excelling. Collaboration time also allows teachers to share ideas for instructional improvement. Many feel this is the most beneficial part of collaboration, exchanging methodology, sharing materials and discussing the assessment results. This often leads to best practices conversations. This time is often built into the daily/weekly schedules of teachers, specialists and school improvement coaches.

Below are additional benefits that were discussed in the seminar regarding collaborating for student achievement:

- Creates a student-centered learning environment focused on standards and achievement.

- Fosters analysis of student work/test results for common misconceptions.

- Increases the opportunities for students to receive consistent terminology, learning strategies and familiarity with the state standards.

- Allows students to gain access to the strengths of all teachers.

- Improves teacher understanding of student weaknesses.

- Creates a district-wide culture on promoting student achievement.

Monday, February 8, 2010

Race to the Top: Preparing to Choose, Implement and Manage Your Local Instructional Improvement System

•instructional planning;

•gathering information (e.g., through formative, interim, and summative assessments;

•looking at student work and other student data);

•analyzing information with the support of rapid-time reporting;

•using this information to inform decisions on appropriate next instructional steps;

•evaluating the effectiveness of the actions taken

Such systems promote collaborative problem-solving and action planning; they may also integrate instructional data with student-level data such as attendance, discipline, grades, credit accumulation, and student survey results to provide early warning indicators of a student’s risk of educational failure (p.9).

The Race to the Top initiative provides a unique, exciting, and timely opportunity for school districts to achieve the goal of elevating student achievement beyond current levels, and to do so in ways that enhance our competitiveness in the global society. Among the many elements that will contribute to success in achieving this goal is the well-informed selection, implementation and management of a high quality local instructional improvement system. In a nutshell, the opportunity to change achievement by the end of each school year is within our reach when we are empowered with actionable information on student learning that helps us to adjust instruction throughout the year. Learning occurs on a daily basis, thus, it is reasonable to assume that the goal of increasing learning can and should be supported one day at a time. A well-designed, research-based, standards aligned instructional improvement system can help to address this need.

As part of our ongoing outreach initiatives to help school districts and states address Race to the Top goals, ATI recently hosted in Colorado a statewide collaborative seminar “Elevating Student Achievement: Exploring What Works”. The goals of the seminar were to:

•Share evidence regarding what is working in districts to elevate student achievement;

•Identify the critical components of effective initiatives built upon the use of an instructional improvement system and aimed at elevating student achievement;

•Discuss challenges faced in initiatives designed to elevate achievement, and the solutions being implemented by school districts; and

•Consider the various management procedures and technology for addressing challenges that may be encountered in implementing programs designed to elevate achievement.

The seminar was attended by school district leaders, educators, and researchers and included presentations by WestEd’s Local Accountability Professional Development Series Project Director (website), the Director of Student Assessment and the Principal Consultant for the Colorado Department of Education Office of Standards and Assessments (website), and Assessment Technology, Inc. (website). Among the successes of this seminar was the formation of grassroots discussion panels comprised of school district leaders in the areas of curriculum, assessment, planning, technology, and evaluation. These individuals often have the responsibility of coordinating the development of criteria for selecting their local instructional improvement system and for implementation and management of the system. Below is a sampling of contextual highlights and questions addressed by panel members:

•An effective instructional improvement system begins with the specification of goals to be achieved within a specified time period. What challenges make it difficult to specify essential standards to be targeted for instruction within a given time period? How can those challenges be addressed effectively?

•An effective instructional improvement system uses formative assessments and a common set of interim assessments within each grade and subject. What challenges make it difficult to adopt common interim assessments and how can those challenges be addressed?

•In an effective instructional improvement system, instruction is adjusted following each interim assessment by implementing re-teaching and enrichment interventions. What challenges make it difficult to implement re-teaching and enrichment? How can those challenges be effectively addressed?

•Implementing an instructional improvement system requires groups of administrators and teachers to work together to provide an assessment system that can be used to inform instruction for all students. What are some of the management challenges associated with designing, scheduling, and implementing customized formative and interim benchmark assessments? What are the challenges associated with designing and implementing curricular interventions based on information about student learning? How can these challenges be met?

•Re-teaching and enrichment interventions require unanticipated allocations of time and resources to the instructional process. How do you meet the challenges of allocating time and resources to re-teaching and enrichment?

If you would like information regarding how panel members responded to these and other questions that emerged during the seminar, please contact us at ATI and/or watch the seminar video to be posted soon on the ATI website. If you would like to share your comments on these challenges within the forum community, please do so here. And, if you have questions that you would like to pose related to instructional improvement systems and the Race to the Top initiative, please post them here for comment from ATI and the forum community.

Jason K. Feld, Ph.D.

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Elevating Student Achievement Seminar - Submit a Question

The seminar will be a dialog on instructional interventions and the elevation of student achievement. If you know of any others in your district interested in registering, please feel free to pass the following link on to them - www.ati-online.com/WhatWorks

We’re also encouraging those interested in submitting a question pre-event for seminar panel discussions on the following topics:

- The benefits of and challenges encountered when implementing an instructional improvement initiative.

- The benefits of and challenges encountered when managing an instructional improvement initiative.

We look forward to hearing your questions!

Thursday, January 7, 2010

So what are item parameters, anyway?

The best way to understand what item parameters refer to is to look at an Item Characteristic Curve. On an item characteristic curve, which presents the data for one, specific item, student ability (based on their performance on the assessment as a whole) is plotted on the horizontal axis, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. The probability of answering the item correctly is plotted on the vertical axis. Typically the probability of answering correctly is relatively low for low ability students and relatively high for students of higher ability.

The first example (Item #4) is an example of a great item as far as the parameters go. The b-value (difficulty) for that item was 0.689, which is a bit on the difficult side, but not too bad. The important point here is that b-values (item difficulty) are on the same scale as student ability. So what this example is telling us is that students at or above 0.689 standard deviations above the mean are likely to get the answer correct. Students below that point on the ability scale are more likely to answer incorrectly. The b-parameter is also known as the location parameter, because it locates the point on the ability scale where students start demonstrating mastery of the concept.

The a-value (discrimination) refers to how well the item discriminates between different ability levels. It’s how steep the rise is in the curve that shows the probability of answering correctly. Ideally, there is a nice, steep rise in the probability of answering correctly like the one for question 4. That indicates that there is a dramatic change in how likely it is that a student has mastered the concept that’s pin-pointed within a very narrow range of the ability scale. You can be pretty confident that students above 0.689 standard deviations above the mean “get it” and that students below that point generally don’t. The discrimination parameter for question 4 is 1.459.

The next example, Item 5, shows an item that doesn’t discriminate quite as well as Item 4. The a-value on that one is 0.53. It’s also a pretty easy item, with a b-value of -1.07. So, on this one, most students are likely to get it correct, unless they’re more than one standard deviation below the mean of the ability scale.